NJORD insight: The new claims procedure of the 2017 FIDIC suite of contracts

About a month has passed since the release of the new FIDIC suite of contracts. The first to publish an article on the conditions was White and Case on the actual date of release, 5 December 2017.

We are now beyond the first impressions and have had some time to review and contemplate on the new FIDIC suite of contracts and the conference where these were introduced and discussed. Considering the scope thereof, I have divided this subject into several articles.

The amendments are numerous, and most amendments are clarifications – clarifications for the better as they are based on 17 years of experience. Much of what was unclear is now clear.

Many commentators agree that the main material changes are:

- a mutual, detailed, and elaborated claims procedure,

- elaboration on the role of the engineer and emphasis on her/his neutrality,

- changes in the scope of liability - in particular relating to “fit for purpose” and “exceptional events”, and

- expansion and elaboration of the dispute adjudication/avoidance board.

At this stage I would also include

5. inclusion of a right to instruct acceleration under the rules concerning variations.

In this article, I will be dealing with 1), 2) and 5) as these are interconnected, and I will present a few recommendations in this regard.

The Claims procedure

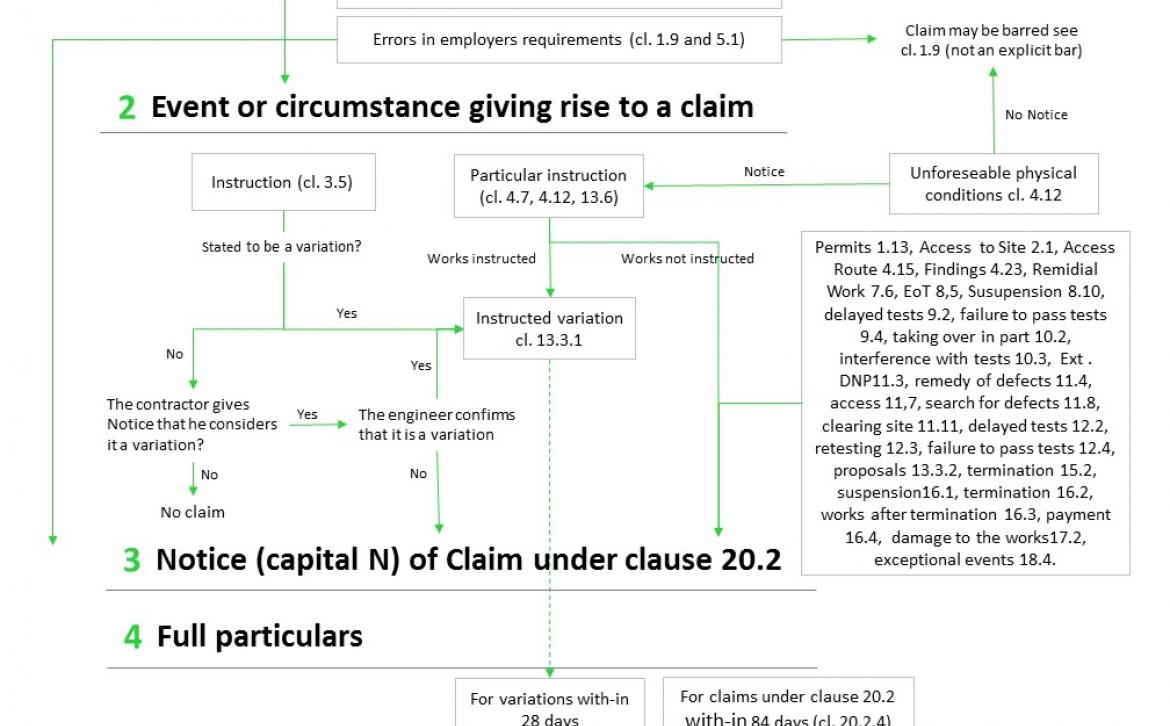

FIDIC has successfully drafted a nearly perfect claims procedure. It may be illustrated as below (the illustration is based on the yellow book).

This detailed procedure is very well drafted and covers all immediate eventualities, but it is complex in written form. However, as the flow-chart illustrates, it is mainly when described in writing that the procedure is complex. The fact that a flowchart (without gaps) can illustrate it clearly proves that the procedure may without great difficulty be partially or fully automated, which is a very interesting prospect.

To me, it remains slightly unclear what happens in the commonly occurring situation when the engineer issues an instruction and maintains the instruction while also maintaining that it is not a variation. I would argue that clause 20.2 applies as clause 13 on variations is intended to apply where the entitlement is not in dispute. However, that is the only vague part of the procedure.

The perhaps largest material change concerning claims is that the provisions have become mutual, which will require some adjustment on the part of the claims handling teams of the employers. For the same reason, it is likely that we will see the employer’s obligations amended by particular conditions.

Considering the detailed drafting and complex wording, I advise caution when making any amendment to the claims procedure.

Further, it is important to be aware that the entire claims system contains several (potential) time bars if proper Notice (with capital N) is not given. One of the requirements for a Notice of Claim is that it must be styled as such.

In relation to Notice my three main recommendations are:

- Employers should take note of the duties to give Notice that they have now.

- Remember to name your notices “Notice (of Claim)” – with capital N.

- Amend with caution.

The Engineer and DAAB

At the London conference, there was a brilliant presentation by Simon Worley on the development of the role of the engineer. Mostly, the new version clarifies the position of the engineer and his tasks and rights and puts these into forms, for instance in relation to the detailed claims procedure.

The position is still that the engineer is hired by the employer and considered part of the employer’s personnel (clause 1.1.32/1.1.33), but the engineer has to act neutrally when making determinations on claims. This wording has been carefully chosen. Whereas the engineer is not and cannot be impartial or indeed be neutral, he may act neutrally.

The yellow book continues to have recourse from the engineer to the DAAB (though now with double A), but DAAB has now also been included in the red book.

Adopting a DAAB or some other means of immediate challenge to the decision of the engineer is a natural step considering that the engineer is not impartial. In many jurisdictions this may even be a prerequisite for the decisions of the engineer to be binding on the contractor.

That is – if there is no recourse to the partial decision of the engineer, the employer’s lack of payment of a claim that is unduly rejected by the engineer may constitute a breach of contract and entitle the contractor to stop the works if so allowed under the contract or the applicable law.

When drafting tender material employers should carefully consider any removal of the DAAB procedure.

Particular Conditions concerning the claims procedure

As set out above it may be worth specifying exactly when the variation and claims procedure applies, but beyond that there are a few amendments to the claims procedure that should be considered.

The inclusion of a right to instruct variations by FIDIC is a step in the right direction. The provisions concerning may, however, be elaborated.

The option to have a third party partake is still not included and the provision does not address the different interests in the acceleration (often the employer’s loss is not equal to the liquidated damages agreed) and the relation to the contractor’s limitation of liability. The contractor may simply assess that it is not worth complying with an instruction to accelerate as it may effectively increase his liability for delay damages and only entail a limited potential upside for him if any.

Further, and related to time is the issue that under the current rules, the contractor is not obliged to comply with an instruction that is a variation. The provision helps manage costs but has the disadvantage that time may be lost waiting for a reply from the engineer as to whether to proceed. It may only be a week, but many instructions fall into this category and a week of delay may lead to a substantial loss. Accordingly, I would include an option to instruct immediate action.

Finally, claims for delay damages because of extension of time (EoT) remain difficult to handle. The issue is that the costs do not arise until long after the circumstances giving rise to the claim and that this particular type of claim often gives rise to great uncertainty in relation to the method of calculation.

To ensure predictability and clarity, I often recommend that a fixed amount for each day (or workday as the case may be) of extension of time is agreed in advance.

I recommend including a more elaborate approach in relation to acceleration and simplifying the issue of claims for EoT costs.